Michael Curtis, MD

University of California, San Francisco

Introduction

Patients with end-stage heart failure that are scheduled for orthotopic heart transplantation (OHT) frequently present with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), such as automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (AICDs) and pacemakers, with or without a cardiac resynchronization therapy function (CRT). AICDs may prevent sudden cardiac death from ventricular arrhythmias that these patients are susceptible to, and pacemakers protect against bradyarrhythmias. CRT may provide both improved cardiac function and symptomatic relief. Given that these are all treating intrinsic properties to the patient’s native heart, CIEDs are typically removed during the intraoperative course of an OHT. Unfortunately, this is not always successfully accomplished – either purposefully or inadvertently – placing the patient at risk of adverse sequelae in the post-operative period.

Incidence of Retained CIED Hardware

Removing a CIED involves extracting the generator itself from its pocket, as well as the leads that most often transverse the subclavian vein to the superior vena cava (SCV) before implanting into portions of the right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV). CIEDs with a CRT function will also have an additional lead positioned in the coronary sinus that will need to be removed. Leads that have been in place for many years, especially for those which include defibrillation coils, may have scar tissue firmly grasping on the leads, which can make extraction a challenging process. Specialized equipment and procedures do exist for these difficult situations, but it is rarely feasible to have all of these tools and skillful operators available during urgent procedures such as an OHT.

Unfortunately, this means that lead fragments are frequently retained after OHT. In fact, multiple studies at a variety of institutions have shown that 16.2-47.5% of patients getting a CIED removed during OHT still had retained material visible on chest radiography post-operatively.(1-4) The large majority of these leads are in the subclavian vein or SVC, but rare cases of migration to RV and even the left ventricle (LV) have been reported.(5, 6) Risk factors for such retained hardware appear to be: age greater than 50 years, the presence of two or more leads, leads that have been in situ greater than 12 months, and the presence of a dual-coil defibrillator lead.(4)

Outcomes from Retained CIED Hardware

This retained CIED hardware does appear to increase the risk of upper extremity DVT, and thus in theory related cardiovascular complications like pulmonary embolism.(3, 7) These hardware fragments may also increase the patient’s future radiation exposure, given both the artifacts they may cause during imaging plus the physical obstruction they may pose when using bioptomes for cardiac biopsies in the post-operative period.(3) This may seem insignificant, but these patients are already at increased risk for malignancies than the general population, and this additional exposure may serve to further elevate that risk.(8)

Although there is theoretical concern about retained CIED fragments becoming infected and leading to bacteremia, especially in such an immunosuppressed population, thankfully studies have found that this is a relatively rare event.(3, 4, 7) There is worry that retained hardware will preclude the use of future MRI scans, or at the very least place those patients at risk of thermal injury in the MRI scanner.(7) While the number of OHT patients with lead fragments getting MRIs has been small, there do not seem to be any reported adverse events.(3, 4) Finally, it is not hard to imagine negative consequences from intracardiac migration from lead fragments, such as cerebral or pulmonary embolism, hemopericardium from ventricular perforation, or major valvular damage. However, none of these events were seen in the rare, reported incidences of this situation.(5, 6)

Looking for Retained CIED Hardware

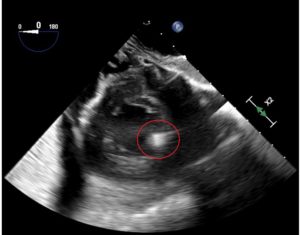

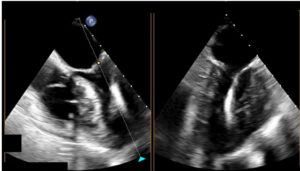

Careful inspection of removed hardware and the surgical field during OHT is the most important and timely method to either ensure that no fragments are left behind or to raise suspicion that challenging to remove segments may have been retained. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) may also be able to detect intracardiac fragments or those in the proximal SVC, though without a high index of suspicion, these fragments may not be immediately obvious (Figure 1 and Figure 2) when focused on evaluating donor heart function and anastomotic sites while coming off cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with tenuous hemodynamics. Even if immediately detected, it understandably might only prompt a discussion with the surgical team about weighing the relative risk of prolonging CPB time versus planning for later removal endovascularly.

However, as discussed above, the majority of these retained CIED leads remain in the SVC or subclavian veins, which cannot be seen on TEE. Thus, evaluating for their presence on post-operative chest radiography still needs to be an important modality to use during the recovery process.

Conclusion

Patients presenting for OHT frequently also need concurrent removal of existing CIED hardware. Due to various factors, retention of hardware fragments, especially dual-coil defibrillator leads, is relatively common and can be associated with negative sequelae such as DVTs or, more rarely, infection if not removed. Intraoperative TEE can play an important role in early identification of intracardiac or proximal SVC hardware, but has limitations in evaluating the locations where retention is most frequent. Fragments can be more extensively visualized on other post-operative imaging modalities such as chest radiography, which should be performed in an expedited manner once the patient is stable. No clear guidelines exist for the timing of removing the leads if found. However, many advocate for them to be removed as soon as possible, typically via endovascular approach, in order to eliminate the ongoing risk of complications.(2)

Figure 1 – Transgastric mid-papillary short axis view on transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) after orthotopic heart transplant (OHT) demonstrating an echodense object at the location of the anterolateral papillary muscle (circled in red above). Additional post-operative imaging clarified that this was a retained cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) lead fragment.

Figure 2 – Concurrent mid-esophageal four chamber and two chamber views on transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) after orthotopic heart transplant (OHT) showing a linear, echodense object extending from the mitral valve to the anterior left ventricular wall (red arrows above). Additional post-operative imaging clarified that this was a retained cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) lead fragment.

References

- Kim J, Hwang J, Choi JH, Choi HI, Kim MS, Jung SH, et al. Frequency and clinical impact of retained implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead materials in heart transplant recipients. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176925. Epub 20170502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176925. PubMed PMID: 28464008; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5413001.

- Kusmierski K, Przybylski A, Oreziak A, Sobieszczanska-Malek M, Kolsut P, Rozanski J. Post heart transplant extraction of the abandoned fragments of pacing and defibrillation leads: proposed management algorithm. Kardiol Pol. 2013;71(2):159-63. doi: 10.5603/KP.2013.0009. PubMed PMID: 23575709.

- Alvarez PA, Sperry BW, Perez AL, Varian K, Raymond T, Tong M, et al. Burden and consequences of retained cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead fragments after heart transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(12):3021-8. Epub 20180424. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14755. PubMed PMID: 29607624.

- Martin A, Voss J, Shannon D, Ruygrok P, Lever N. Frequency and sequelae of retained implanted cardiac device material post heart transplantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(2):242-8. Epub 20140115. doi: 10.1111/pace.12274. PubMed PMID: 24428516.